by Emma Joy | Mar 28, 2022 | From The Rocking Chair, Uncategorized

Some of what we are witnessing is the fallout from what it means to be expected and to expect oneself to operate at high levels of excellence and achievement, while at the same time contending with the constant public scrutiny of those who play out their lives through the public performance of actors, athletes and artists and the transactional demands of fans and entertainment industries. Public performers are-as much as we would like to ignore-human beings subject to the same heights of achievement, depths of feeling, experiences of trauma, failures and frailty that we all experience. The scrutiny and energy that is projected onto them must take a toll.

When public actors do not live up to our projected expectations some of us respond as if we are bystanders on a school yard playground egging on the fight for our own amusement and entertainment; others of us who are affected by histories of trauma are triggered and wish the same punishment on these public actors as we would like meted out to those who have caused us pain. Finding healthy resolutions to conflict amid the constant barrage and pummeling of public commentary, hero’s praise or death wishes, without adequate boundaries, constraint and sage wisdom to guide the process will be difficult if not unlikely. The arguments that ensue, the judgments unleashed, and sides taken eventually overtake social media actors’ and consumers and sweep us all into a swell of dis-ease and states of depletion of what is needed to remain grounded and in tune with who we are and who we are meant to be.

Acknowledgment and accountability are necessary for true healing and reconciliation. Healing and reconciliation are more likely to take place outside of the public gaze of those intent on keeping score, stoking the embers of conflict or not yet ready to forgive even when those primarily involved have acknowledged the injury, attempted to make amends and have moved on. To light the path to justice and healing, be prayerful and ponder the best way to use your energy in light of all of the energy that is being projected and unleashed in the current moment.

by Emma Joy | Oct 17, 2021 | From The Rocking Chair

My mother has frontal lobe dementia. Recently, I took her in to see her neurologist at her Elder Care Center to discuss changes in her behavior. Her neurologist, Dr. Lerner, introduced us to a young doctor who was assisting him. As he reviewed Mom’s case history with his young colleague, Dr. Lerner began to recount our journey together over the years. He described how he and I first met and what those early encounters with Mom were like. At one point, as he was watching me working to direct and re-direct my mother as she was moving around the examination room, Dr. Lerner smiled and summed up his observations of us by saying, “you see, this is really a love story.”

When family members and friends began to be concerned about her behavior, my mother was living by herself in our hometown in Indiana. All of her children—my two brothers and I—lived out of town. I started driving back and forth to check on her and to try find out what was wrong. We visited doctors and scheduled tests but no one could tell us what was causing these changes. Dr. Lerner was the first one to give us a name for her illness. After the diagnosis, we brought my Mom to live with me in Ohio. Dr. Lerner and the Center provided services for us and helped me to navigate those early years with Mom and the reality of caregiving.

Caring for my mom and providing the best quality of life that I could for her became the central concern of my day to day life. It was a real battle at first. Mom didn’t think that anything was wrong with her. She thought that she could still live on her own and take care of herself. While it was difficult and there were days when I felt like I had come up short as a caregiver, after a time, my mom reconciled with being cared for and generally moved through life with an air of sweetness and joyfulness that was core to who she is as a human being, as a woman, and as a mother.

Dr. Lerner’s recollections and proclamation reminded me of the first time I looked at my mother after a hard week of caregiving that included battles to bathe her and change her clothes and worries about how to deal with dental appointments and shots with her changing moods and short attention spans and, suddenly, I saw a light in her. In that moment, I felt awash in the fullness of her beauty. I identified with her vulnerability and laughed at her joy and her tenacity in the face of a life changing illness and I said to myself, “You are the love of my life!” I then recalled a picture of her as a young mother holding me—her first born child—and I realized that this is what she must have felt about this vulnerable, needing bundle of life she had brought into the world. I fell in love with my mother all over again amid the changing dynamics in our relationship in which I was now responsible for her health and wellbeing.

I now understood the heart ache that is a part of every love story when the one you love hurts. I accepted the disappointment that you can feel in yourself and in each other as par for the course. Even though I knew that Mom’s behaviors were a result of her disease, there were times when I was triggered by old wounds and unresolved issues. Sometimes I felt guilty for not doing enough, not being enough for her and for her life now. There were times when I became angry and impatient. I felt guilty for that too. But there were also those times when my mother looked at me and tears welled up in her eyes and even with the advanced aphasia she let me know that I am a good daughter, that she loves me for caring for her, for centering her in my world. And then the love that we feel toward each other would wash away all of the uncertainty and the pain. My mother still looks at me that way and often takes my hand to dance with me and laugh. For me, this is a celebration of the love we continue to share as a mother and a daughter.

My mother is indeed the love of my life. Through the love, the guilt, even the anger my mother is always teaching me, preparing me for the work that I need to do in the world. She taught me that no matter how hard things get, that I need to show up in the world energized not defeated. In caring for my Mom I learned that the anger and the guilt I felt were fundamentally about fear—fear of loss, fear of failure, fear that I wouldn’t make it through the low points of the journey. My mother taught me how to dance and be joyful daily even when the work of living becomes difficult. My mother is still teaching me how to love through it all and I am healed and redeemed by this opportunity to return the unconditional love my mother first gave to me.

What is Love teaching you today?

by Emma Joy | May 30, 2020 | From The Rocking Chair

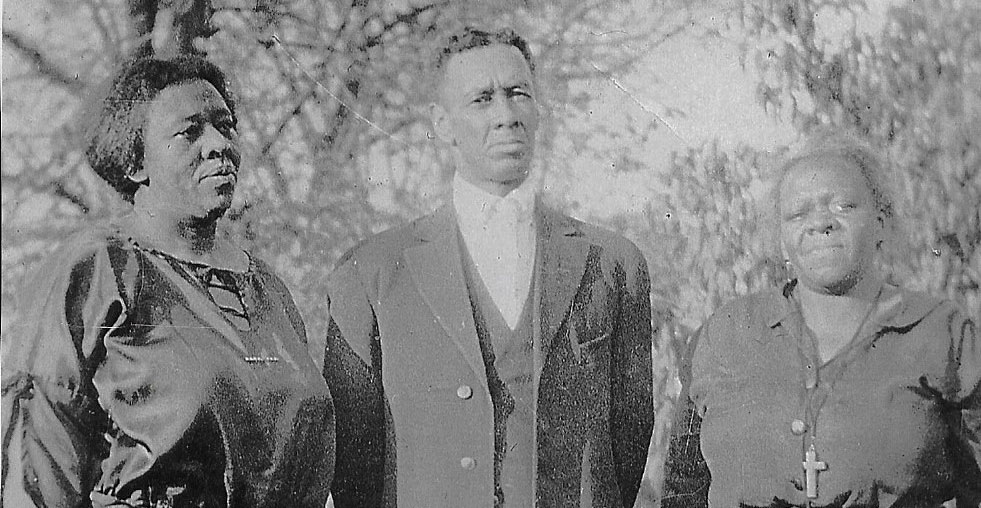

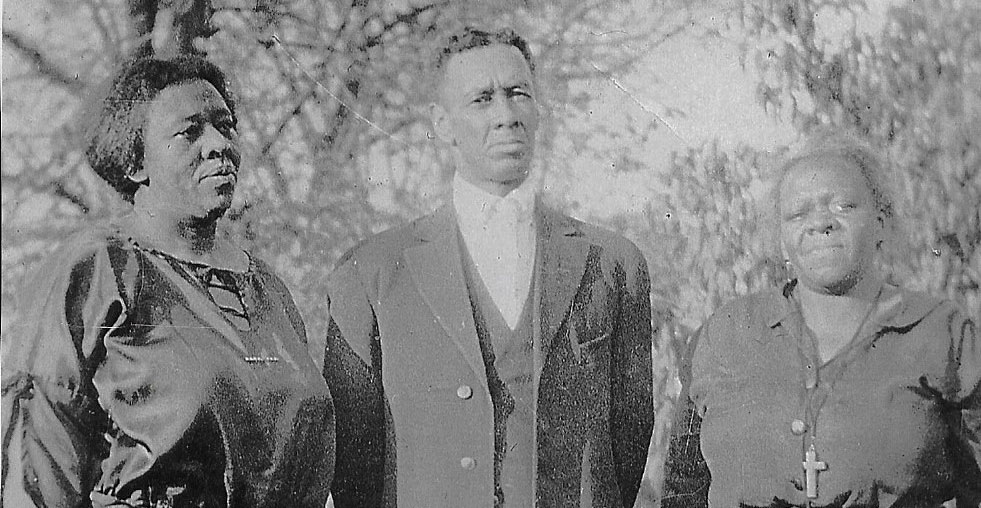

My paternal grandfather’s family is from Grenada, Mississippi. My grandfather left the South in his late teens and never talked about his years growing up there. Years after my grandfather died, I reconnected with one of his cousins. When I visited her, she shared family stories with me. Over time, I discovered that my great-great grandmother, Emma, was a healer and a midwife. Emma and her mother, Priscilla, owned land in the segregated South. This land was in our family for at least five generations. They also owned a farm outside the city where they grew vegetables. They sold the produce to members of the community at a roadside stand. Emma was also a seamstress. She would make white dresses for the church mothers who couldn’t afford department store prices for their church uniforms. The family worshipped at Belle Flower Missionary Baptist Church which was one of the headquarters for mass rallies and civil rights meetings during the 1960s. The church was only a block away from their home. Emma and Priscilla cultivated herbal remedies and spiritual technologies to tend to the needs of blacks and poor whites who could not afford to go to a doctor or to the hospital. These remedies and technologies were influenced by indigenous practices used in African American and Mississippi Choctaw traditions. Thus, my grandmothers cultivated extra-institutional ways of caring for, and restoring individuals and the community to health.

My grandmothers didn’t waste anything. They used and repurposed material items to sustain the community and its ecological networks. To support her vocation, Emma’s husband, Pickens, hand carved a rocking chair that fit Emma’s six-foot frame. Emma rocked each baby that she delivered in this rocking chair as a part of their birthing ritual. While she worked in the community as a midwife and healer, Emma also took in and apprenticed young women whose parents had disowned them because they were pregnant and unmarried. She restored these women to their rightful place in community and gave them a purpose and an important role in communal life. In this and other ways, my great grandmothers were not only midwives who facilitated birthing rituals but they were also warrior-healers. Social justice activist and civil rights attorney Fania E. Davis describes warrior-healers as those who facilitate communal justice, restoration, and systemic transformation.[1]

From the Rocking Chair carries on the traditions of midwives, warriors, and healers like my great grandmothers who work in solidarity with those who are marginalized to generate and apply strategies, systems, analyses, prescriptions and practices that enable individuals to give birth to present and future possibilities; engender systemic change; and bring about healing and wholeness to the planet and its inhabitants. The work of community building, justice, and restoration begins with both personal and collective self-reflection and accountability. Knowing our family stories and histories helps to equip us to do this work more effectively.

Invitation: As a part of your own self-reflection, ask some of the elders in your family or community to share stories of your family’s migrations or ancestral memories. Oftentimes a particular family member keeps the family history so you may want to start with them. What do these stories reveal about certain strengths, gifts or tensions in your family? How do these stories call for celebration, healing, reconciliation, or restoration? How do these stories inspire you to act or spark your imagination? Please note that asking some elders about the past and uncovering ancestral memories may trigger issues of trauma or bring up unresolved anger or hostilities. Family members may more readily share memories during mutual experiences or creative tasks like looking at photo albums, cooking, dining, walking, barbecuing, or quilting. In this time of social honoring you may find letter writing, phone calls or “FaceTime” more appropriate. Respect the fact that some elders may not want to talk. Don’t push. Be patient and gentle. Seek support when you need it. Below are some resources you might want to use to support you as you reflect.

[1] Davis, Fania. The Little Book of Race and Restorative Justice: Black Lives, Healing, and US Social Transformation. New York: Good Books, 2019. p 71.

Resources

Resmaa Menakem. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas: Central Recovery Press, 2017.

https://www.resmaa.com/about and https://www.resmaa.com/resources

by Emma Joy | May 24, 2020 | From The Rocking Chair

How do we address white body supremacy trauma? Resmaa Menakem argues that we can address the pain in “clean” and “dirty” ways.[1] “Clean” pain is pain from trauma that individuals and communities acknowledge and confront historical trauma honestly. Individuals and communities act out “dirty” pain by rejecting a clear-eyed view of the historical traumas and by detaching themselves from responsibility or accountability and the racialized violence and pain they have witnessed, enabled, and produced. When acting out dirty pain, white folks drawing upon white body supremacy try to “soothe” the pain of unmetabolized trauma and the dissonance with more powerful white bodies coursing through their bodies, by blowing it through “Other” bodies—black bodies, brown bodies and perceived “foreign” bodies. Examples of choosing “dirty pain” and unleashing the trauma of these terror-based systems include the erection of Confederate statues to assert white supremacist power, and brandishing assault rifles in coffee shops and state houses as a “right” or an entitlement under the protection of law enforcement. Whites who identify as liberal or even progressive are not immune from acts of white entitlement and racialized violence. Whites of all political spectrums may choose to weaponize law enforcement or self-deputize to intimidate, detain or annihilate by way of extrajudicial killings free, “self-managing”[2] black bodies. This need to annihilate the perceived threat of free black people who will not service or yield to white assertions of power or who will not soothe white guilt or absolve white responsibility for racialized trauma speaks to the nature of white body supremacy, and its relationship to both a perceived white privilege and the identification of racist ideology with “normative” culture. This need to annihilate the “Other” rather than confront one’s own racial history, complicity in racialized violence, and embodied trauma also speaks to the perceived necessity of white supremacists and their allies have to dispatch with empathy and to sacrifice others—by way of projecting blame, annihilating, harassing, terrorizing, incarcerating, deporting, dismissing and rendering invisible—to temporarily soothe the economic and social dissonances of their own lives and avoid confrontation with the poisonous nature of white privilege.

Gaining a better understanding of how white body supremacy can infect the body helped me to see how our family and other black folks in my community have been able to survive and even thrive despite white supremacist efforts at annihilation. My grandmother and the other elders in our family chose to largely engage in “clean” practices that confronted and metabolized much or at least some of the pain of white body supremacy trauma and passed on ethical traditions, tools and techniques for resiliency. They told us stories and passed on words of wisdom that grounded us in our own bodies and the realities of racism. We were taught to demand justice and dignity. We participated in the music, the hymns and congregational singing of the black church, the moans of the blues and the joy of soul music, jazz, funk and R & B. The running of sound through our bodies[3] by way of speech and song grounded us in a humanity that demanded mutual respect and dignity. My family emphasized education and hard work. My grandmother was an example and she gave us the blue print. She became a hair dresser and built a cosmetology business that serviced blacks and whites in her southern town and later in the North. She was a musician and choir director for local churches. My Sunday School education in our family church emphasized close reading of texts. We were taught how to ask questions, listen to others and develop rhetorical strategies for respectful debate. I had opportunities to give speeches and formulate arguments and listen to the reasoning of others. This taught us to debate with compassion and courage. We were given avenues to develop and play with our individuality and were deeply affirmed in our identities as we came in to our own. There were, of course, limits to this affirmation. Our community institutions and elders often reinforced patriarchy and heteronormativity. But we were also taught that we are a part of a collective and mutual respect and dignity are the foundations of a God-given life. We were learning and drawing from traditions that black folks carried with them across the generations. These Sankofa practices are what enabled us as a family and the communal circles to which we belong to metabolize the trauma of white body supremacy, in clean ways in order to find healing and create our own spaces to thrive. But this doesn’t mean that racialized trauma has not and still doesn’t take its toll.

Sankofa is an Adinkra symbol and concept. [4] In the Twi language of the Akan, Sankofa literally means “go back for what you have forgotten.” Sankofa practices are based on a worldview in which all of life is interrelated. The elders—those who have demonstrated an ethical commitment to the earth and the community—pass on tools and wisdom traditions that support mutual respect and dignity for individuals and the community. To be sure there are black people who are among those who have adapted “dirty” ways of dealing with unmetabolized pain and trauma such as internalized racism, colorism, forms of corporal punishment that echo slaver narratives of punishment, and the need to soothe white peoples’ fears by aligning themselves with white power.[5] Alternatively, Sankofa practices are meant to break the power of historical trauma, address the clean flow of pain through the body and facilitate healing. These tools and traditions provide ways to confront trauma and death-dealing historical events and avenues for personal and social transformation.

As a country, we have failed to effectively acknowledge and confront the historical trauma of indigenous genocide, the enslavement of African people, and the demonization of darker skinned immigrants. While a few exceptions exist such as the Lynching Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama we have largely dealt with these oppressions by building monuments to individual exceptionalism and speaking platitudes of inclusion. In order to effectively address the historical and racialized trauma that impacts their and our lives, white folks need to reject dirty pain responses and choose the “clean” and hard work of metabolizing this trauma by honestly confronting historical racism and acknowledging the role that they, their families and the institutions and people with which they have been aligned have played and continue to play in the oppression and brutalization of others. It also means to work in solidarity with the primary victims of white body supremacy and being able to imagine themselves in the shoes of others. Being in solidarity means acknowledging the evil that is white supremacy and their own role in its perpetuation. It means to understand the ways in which the trauma of white body supremacy has impacted their own lives and the lives of their family and friends. It also means acknowledging and rectifying the white body supremacy trauma they have caused by direct action, passively witnessing or remaining silent. This includes recognizing the ways in which white body supremacy has become the equivalent of identity and culture and the toll that has taken on their own lives and the lives of their own family members and the institutions to which they belong. Additionally, it means to deal honestly with the dissonance between working class white people’s lives and white elites by confronting the power wealthy whites exact over their lives and holding them accountable rather than projecting this dissonance onto the lives and bodies of black people or those deemed vulnerable or expendable. Finally, it means to develop culture in which whites are accountable to repair the damage of the trauma white body supremacy has caused to black and other dark skinned people.

Invitation: I would like to invite you to continue to work through Cultural Somatics Institute’s Free Racialized Trauma 5-day eCourse at the bottom of the web page https://www.resmaa.com/. Try to move through those sessions directly related to groups of which you are not a part. Again, try to get plenty of rest and drink plenty of water as you engage in this course and find support when you need it. Feel free to pause and rest.

[1] Resmaa Menakem. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas: Central Recovery Press, 2017. pp 165-167.

[2] Ibid., p 28.

[3] Bernie Johnson Reagon. Bill Moyers Journal. http://www.pbs.org/moyers/journal/11232007/profile3.html. November 23, 2007.

[4] Adinkra symbols are symbols that represent proverbs of the Akan people of the southern part of Ghana in West Africa.

[5] Menakem. p 167.

Resources and Further Reading

Robin Diangelo. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism. Boston: Beacon Press, 2018.

Kelly Brown Douglass. Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books.

Resmaa Menakem. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas: Central Recovery Press, 2017.

Jonathan Metzl. Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America’s Heartland. New York: Basic Books, 2019.

by Emma Joy | May 17, 2020 | From The Rocking Chair

After the mass murder of nine members of the historic Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal church in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015 by an avowed white supremacist, local governments throughout the country began taking active measures to remove Confederate statues from public property. Many of these statues were erected to assert white supremacy and justify segregation during times of increased civil rights activism. Now white supremacist and pro-Confederate demonstrations were held to challenge the removal of these monuments. As I watched the news, a reporter interviewed one particular protester, a man in his thirties. When he was asked why he wanted to celebrate a Confederacy that fought for the inhumane enslavement of African Americans and the expansion of slavery to other states, the protester responded by saying “I don’t care about slavery.” He was demonstrating to protect his heritage he said. His response was fundamentally one of grievance. “My family were sharecroppers. We built the South.” I was struck by his callous attitude toward the enslavement of others and the experience of human suffering. I was also struck by the way he romanticized the system of sharecropping and aligned himself with the powerful white elite in his claim to white privilege.

My maternal grandmother was a sharecropper in Mississippi. Her children and grandchildren were under no illusion regarding the cruel and exploitive nature of the sharecropping system and who it benefited. We were clear eyed about the violence of racial segregation and white supremacy. The sharecropping system was designed to keep workers like my grandmother indebted to landowners. Although my grandmother didn’t speak of it often, she told me stories about the harsh realities of growing up in the Jim Crow South and the relationship of Jim Crow laws to the system of slavery. She described working in intense heat and how she was constantly pricked and scratched by thorns to the point that she had to bandage her bloody feet and keep working in the hot sun. Poor people (black and white) like my grandmother didn’t go to high school. They typically started working in the fields after completing the 8th grade. My grandmother didn’t have access to child care. She had to leave her children unattended while she worked. When Emmett Till was brutally murdered in 1955, my grandmother left Mississippi with her family and moved to the North because she was afraid that one of her nine children might one day meet the same horrible fate.

As I watched this man who was so determined to celebrate, to the detriment of other human lives, a Confederate system and wealthy whites who participated in the exploitation of his own family’s labor, I remember thinking that this man has more in common with my family then the powerful whites he was defending. While I understood the ideology of white supremacy as a terror-based system that inflicts trauma onto its targets and bestows privilege according to perceived racial “membership,” I still could not fully wrap my mind around the disconnect between this man’s worldview and the way in which land owners exploited his family. Suddenly, I flashed back to footage of the Emmett Till murder trial. White men lined the sidewalk and peered out of windows outside the courthouse. The men who murdered Emmett Till held and played with their young sons. These were working class men who were well aware of the power of their whiteness and were using it in an attempt to intimidate Till’s family members and members of the black community. The men were grinning and talking with their sons as if they were teaching them, schooling them in the power of white supremacy. They had brought their sons to witness how systems of white supremacy worked. These men bonded with each other and with their sons over the power they could wield against black people and black bodies and the violence they could exact with impunity. This violence was enabled by the legal system and law enforcement. I could tell the boys enjoyed being fawned over by their fathers but I wondered how these young boys processed the abuse and violence involved. I wondered had this protester against the removal of Confederate monuments participated in these types of white supremacist bonding rituals with members of his family or community institutions. It is clear that this is at least symbolic of the ways in poor and working class whites may bond with each other and assume a bond with the powerful, elite whites who had inherited wealth and status from their fathers.

While it is clear that racial animus and the desire to claim white identity as a means to assert racial privilege motivates many white folks to hold onto a deeply distorted view of U.S. history, I must admit that I am still confounded by the ways in which working and middle class whites who embrace white supremacist ideologies choose again and again to act even against their own self-interest in order to align themselves with the wealthy. I have started thinking more about historical trauma, white supremacy and the connections between historical trauma and white violence in making some sense of this. As a country, we have done little to address the historical trauma of racialized violence we have inflicted and experienced in this country nor have we adequately dealt with the structural impact of systematic, historical, and racialized trauma. Resmaa Menakem’s book My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending our Hearts and Bodies has helped me to better understand another component to the fallout of historical trauma in this country. While I understood and worked with some techniques regarding how trauma shows up in the bodies of black survivors of violence and oppression, I needed to do more work to understand the ways in which white body supremacy infects white bodies.

Menakem describes “white-body supremacy” and its trauma as something that inhabits all of our bodies and is integrated into structures and systems within all of our communities. [1] White body supremacy takes up residence in black, brown, and white bodies. Therefore, discursive approaches to confronting racism and white supremacy, while critical and necessary to the work of anti-racism, can only go so far. It is also important to address the ways in which racialized trauma inhabits the body. Let me be clear, racialized trauma deeply impacts the primary targets of terror and violence. It is those who are the primary target of racial violence and witnessing members of the targeted community who are in need of immediate and ongoing support, and for whom we must find justice. When current acts of racialized violence occur, these primary targets are the priority. But if we are to engage in efforts to bring about broader systemic changes, work should also be done to address what Menakem refers to as the secondary trauma of witnessing and inflicting pain and the unmetabolized trauma in the body.[2] White supremacy is rooted in an abusive belief system. It is authoritarian in nature. Parental and institutional authoritarian power wielded by church leadership and fraternal societies shaped by practices of white body supremacy pass abusive belief systems, violence and entitlement off as culture sanctioned by a vindictive god. Whites who monopolize resources and abuse power know how to trigger white animus and white grievance (encased in unmetabolized trauma) among poor, middle, and working class whites. Whites who cling to alternative white supremacist histories and authoritarian power are dependent upon those who occupy positions of power for validation. These are the historical or symbolic descendants of the pre-Emancipation southern aristocratic class. Rather than act in solidarity with black and brown people of similar socioeconomic groups to change systems and structures that do not serve them and confront abusive power, these whites align themselves with white supremacist structures and the attending white privileges to, themselves, exercise sanctioned forms of abusive power over black and brown people in order to “soothe” their own social and economic fears and to soothe the “dissonance” between them and wealthy whites. [3]

Invitation: I would like to invite you to start the Cultural Somatics Institute’s Free Racialized Trauma 5-day eCourse at the bottom of the web page https://www.resmaa.com/. The first session will help you to start to assess symptoms of historical, intergenerational, or institutional trauma in your life or in others who are close to you. Subsequent sessions address trauma in black bodies, white bodies and police bodies. Try to get plenty of rest and drink plenty of water as you engage in this course and find support when you need it. Feel free to pause and rest.

NEXT Sankofa & Solidarity (Part II): Historical Trauma and Solidarity Practices

[1] Resmaa Menakem. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas: Central Recovery Press, 2017. p 10.

[2] Ibid., p 46. Menakem also argues that whites need to contend with intergenerational trauma that is rooted in torture techniques Europeans used on one another dating back to the Middle Ages. pp 58-63.

[3] Ibid., p 63.

Resources and Further Reading

Robin Diangelo. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism. Boston: Beacon Press, 2018.

Kelly Brown Douglass. Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books.

Resmaa Menakem. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas: Central Recovery Press, 2017.

Jonathan Metzl. Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America’s Heartland. New York: Basic Books, 2019.